Oeufs Vanity Fair

Soft-boiled eggs

It may seem odd to write out a recipe for soft-boiled eggs, but that is exactly what Crowley did, and in a manner to elevate them with a French name, Oeufs Vanity Fair. The recipe reads:

Oeufs Vanity Fair

Take 2 hen’s eggs, new laid

1 quart water

Boil the water in a saucepan; when boiling place the eggs in it, and keep the boil for 3 1/2 to 4 minutes. Remove the eggs, take off a portion of the shell, and eat the inside of the egg with a spoon. ~Aleister Crowley~

To explain why he might have felt the need to include a recipe for something so obviously simple, one must remember the era into which Crowley was born. As a late Victorian and early Edwardian and as landed gentry, Crowley entered the world in an era where the upper middle class (as he was) would have staff to prepare his meals and clean his clothes and belongings. In this strata of genteel refinement, he was not quite the level of - say - a Downtown Abbey like household with under-butlers and scullery maids. But most middle class households would employ a cook, if nothing else. The proper English could vary from the expansive (to include blood sausage or rashers, eggs, toast, porridge, and fish, such as kippered herring or smoked salmon) to the moderate (toast, eggs, and porridge). And tea. There was always tea.

What we now know as fried eggs when then called buttered eggs often served atop toast. However there is a finery and ritual to consuming a soft-boiled egg that involves specialty cutlery; the egg cup and spoon. Knowing how to appropriately tap the top edge of the egg to remove its crown and deftly scoop out the insides to eat showed society that one was well-bread and understood the specificities of etiquette. Much of the reason for specialized cutlery established during the Victorian era was to help differentiate those who were raised in “proper society,” and the nouveau riche who had risen through the ranks without the skills to appropriately peel an orange with a fruit knife, or sever the adductor muscle of an oyster with an oyster fork.

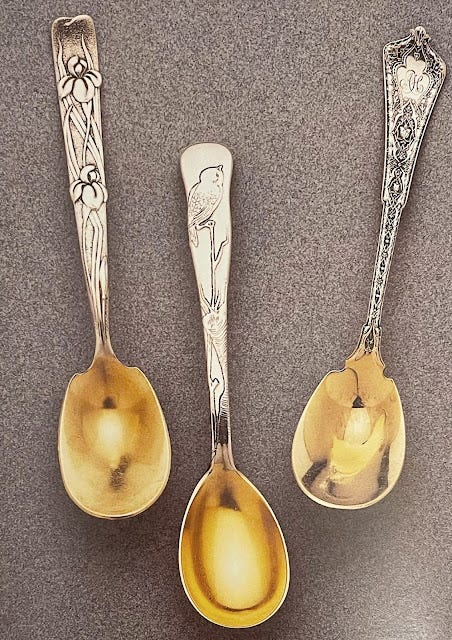

A soft-boiled egg would be served in a silver egg cups (sterling if you were wealthy enough, and plated if you just wanted to pretend you were wealthy enough). The spoon which accompanies the cup is not a standard teaspoon, but a tad smaller — usually four to five inches in length — with a slightly oblong bowl that can expertly fit into the bottom of the egg. Often, as in these Tiffany egg spoons, the bowl of the spoon would be gilded in gold to keep the spoon from discoloring that can occur from the sulfur which emanates from eggs.

Back to the question at hand: Why would Crowley have written out a recipe for something so simple? My supposition is two-fold: First, having grown-up with someone who would have prepared his breakfast, and later had breakfast presented to him along with classmates at boarding school, this was an everyday dish he would likely wish to eat himself. During his early Paris years, restaurants were open for lunch and dinner, but not for breakfast (except if one is staying in a large enough hotel). Crowley had a private flat in Paris and it is assumed he did not employ a cook, based on the number of meals he ate out later on in the day. Being one who documented almost everything in his life, penning the instructions for a soft-boiled egg was just another step towards an orderly, organized life.

That his “recipe” mirrors that of the great Isabella Beeton who penned The Book of Household Management; a massive tome of recipes of household hints. First published in 1859, it was republished and added to so that, by 1907, it consisted of 74 chapters and was more than 2,000 pages long. This book was Julia Child, The Joy of Cooking, Betty Crocker, and more, all in one massive, eight-pound book. Undoubtedly Crowley glanced at it, for here is Mrs. Beeton’s version of the soft-boiled egg:

TO BOIL EGGS FOR BREAKFAST

Eggs for boiling cannot be too fresh, or boiled too soon after they are laid; but rather a longer time should be allowed for boiling a new-laid egg than for one that is three or four days old. Have ready a saucepan of boiling water; put the eggs into it gently with a spoon, letting the spoon touch the bottom of the saucepan before it is withdrawn, that the egg may not fall, and consequently crack. For those who like eggs lightly boiled, 3 minutes will be found sufficient; 3-3⁄4 to 4 minutes will be ample time to set the white nicely; and, if liked hard, 6 to 7 minutes will not be found too long. Should the eggs be unusually large, as those of black Spanish fowls sometimes are, allow an extra 1⁄2 minute for them. Eggs for salads should be boiled from 10 minutes to 1⁄4 hour, and should be placed in a basin of cold water for a few minutes; they should then be rolled on the table with the hand, and the shell will peel off easily.

Time.-- To boil eggs lightly, for invalids or children, 3 minutes; to boil eggs to suit the generality of tastes, 3-3⁄4 to 4 minutes; to boil eggs hard, 6 to 7 minutes; for salads, 10 to 15 minutes.

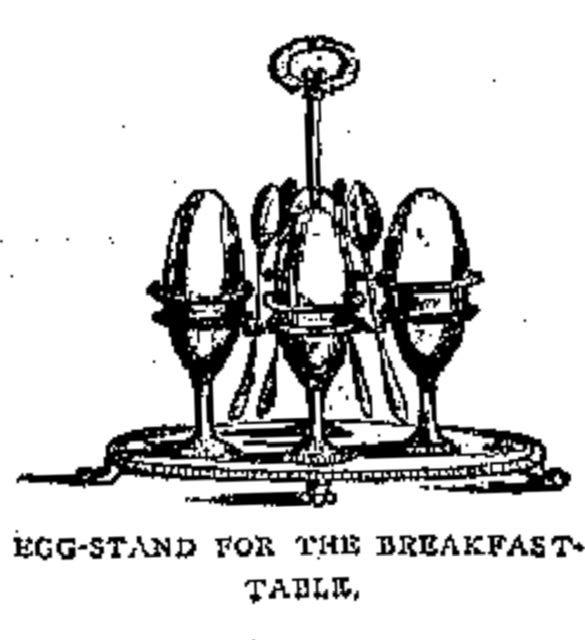

Note.-- Silver or plated egg-dishes, like that shown in our engraving, are now very much used. The price of the one illustrated is £2. 2s., and may be purchased of Messrs. R. & J. Slack, 336, Strand.