Ernest Hemingway's "A Moveable Feast"

Paris, 1921

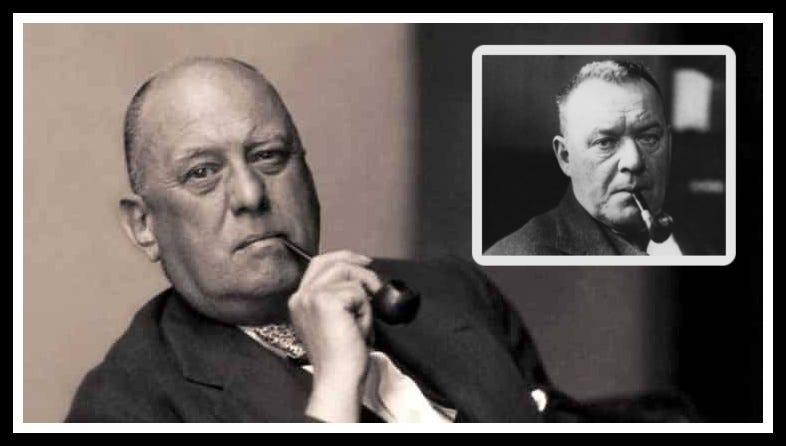

When researching Aleister Crowley’s gastronomic endeavors, instead of following a linear biographical location, I jumped into his Paris years, but in a back-handed way; by starting with Ernest Hemingway’s memoir penned in the 1920s, but not published until after his death in 1961, A Moveable Feast. While Crowley himself had written extensively about his Paris magickal and gustatorial escapades, I was curious how others in the literary community reacted to Crowley’s existence.

The 1920s in Paris was a creative hub for artists, writers, and poets from all the world. Known as the Lost Generation, they were born between the late 1880s to 1900, and came of age during World War I; too young to have served, but not too young to have suffered its impacts. The moniker was ascribed by the great Gertrude Stein herself, when speaking to a young Hemingway, as she laments an overall absence of traditional values and loss in faith by the intellectuals and creatives who embraced hedonism and abandonment of social mores. It might be said that Crowley was cut off the same cloth, but while he may have embraced a life of debauchery, his dedication to ritual and study implies characteristics of a belief system — albeit of his own making — that was want in this younger generation.

Ernest Hemingway was only 22 years old when he came to Paris in 1921. Crowley, then 46, was more than twice his age at that point; well-established and well-published. Fledgling writer Hemingway, as a foreign correspondent, had only published articles for the Toronto Star, but was working on his first novel, The Sun Also Rises, eventually published five years later in 1926. Until then, he would spend many afternoons writing in Parisian street cafés: “The blue-backed notebooks, the two pencils and the pencil sharpener (a pocket knife was too wasteful), the marble-topped tables, the smell of early morning, sweeping out and mopping, and luck were all you needed.”

It was at these cafés or the nearby bars, where Hemingway began meeting the other literati of the era: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Ford Maddox Ford, James Joyce, and of course Gertrude Stein. Through Stein and her famous salons, he met noted modernist artists Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, Henri Matisse and Joan Miró. Hemingway’s relationship with Ford Madox Ford was instrumental for both gentlemen. While Ford was known for his own novels and poetry, he catapulted many fledgling writers with his publications of The English Review and The Transatlantic Review, the latter which Hemingway helped edit. Living at 113 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, Hemingway was especially fond of the nearby café, Closerie des Lilas, citing it as one of the best cafés in Paris, and where he and Ford often met:

“I took another long drink. The waiter had brought Ford's drink and Ford was correcting him. 'It wasn't a brandy and soda,' he said helpfully but severely. 'I ordered a Chambery vermouth and Cassis.' 'It's all right, Jean,' I said. 'I'll take the/w. Bring Monsieur what he orders now.' 'What I ordered,' corrected Ford.

At that moment a rather gaunt man wearing a cape passed on the sidewalk. He was with a tall woman and he glanced at our table and then away and went on his way down the boulevard.

'Did you see me cut him?' Ford said. 'Did you see me cut him?'

'No. Who did you cut?' 'Belloc,' Ford said. 'Did I cut him!' 'I didn't see it,' I said.

'Why did you cut him?' 'For every good reason in the world,' Ford said.

'Did I cut him though!'

He was thoroughly and completely happy. I had never seen Belloc and I did not believe he had seen us. He looked like a man who had been thinking of something and had glanced at the table almost automatically. I felt badly that Ford had been rude to him, as, being a young man who was commencing his education, I had a high regard for him as an older writer. This is not understandable now but in those days it was a common occurrence.

I thought it would have been pleasant if Belloc had stopped at the table and I might have met him. The afternoon had been spoiled by seeing Ford but I thought Belloc might have made it better.

'What are you drinking brandy for?' Ford asked me. 'Don't you know it's fatal for a young writer to start drinking brandy?' 'I don't drink it very often,' I said. I was trying to remember what Ezra Pound had told me about Ford, that I must never be rude to him, that I must remember that he only lied when he was very tired, that he was really a good writer and that he had been through very bad domestic troubles. I tried hard to think of these things but the heavy, wheezing, ignoble presence of Ford himself, only touching-distance away, made it difficult. But I tried.

'Tell me why one cuts people,' I asked. Until then I had thought it was something only done in novels by Ouida. I had never been able to read a novel by Ouida, not even at some skiing place in Switzerland where reading matter had run out when the wet south wind had come and there were only the left-behind Tauchnitz editions of before the war. But I was sure, by some sixth sense, that people cut one another in her novels.”

The “Belloc” to whom Hemingway is referring was Hilaire Belloc who, very much like Crowley and of the same generation, was a man of many talents, literary and otherwise. He was a soldier and a poet, a sailor and a satirist, and a well-known historian. Born in France in 1870, he became a naturalized British citizen, but maintained his French citizenship. A devout Catholic, Belloc’s sardonic wit is easily seen influencing the likes of Edward Gorey, with his highly acclaimed Cautionary Tales for Children which included stories such as: "Jim, who ran away from his nurse, and was eaten by a lion," and "Matilda, who told lies and was burned to death" Why am I telling you about Belloc when we were discussing Hemingway and Ford, but this is supposed to be about Crowley? Well let us continue with Hemingway’s tale…

After Ford left it was dark and I walked over to the kiosque and bought a Paris-Sport Complet, the final edition of the afternoon racing paper with the results at Auteuil, and the line on the next day's meeting at Enghien. The waiter Emile, who had replaced Jean on duty, came to the table to see the results of the last race at Auteuil. A great friend of mine who rarely came to the Lilas came over to the table and sat down, and just then as my friend was ordering a drink from Emile the gaunt man in the cape with the tall woman passed us on the sidewalk. His glance drifted towards the table and then away.'That's Hilaire Belloc,' I said to my friend. 'Ford was here this afternoon and cut him dead.'

'Don't be a silly ass,' my friend said. 'That's Aleister Crowley, the diabolist. He' supposed to be the wickedest man in the world.'

'Sorry,' I said.

All things considered, knowing Belloc and Crowley were contemporaries, roughly the same age and demeanor, and wandering the same Parisian streets, seeing them here together, it is easy to understand how the mistake may have been made.