Let's Talk Turkey

Happy Solstice, 2023

Whether one decorates a tree, lights a menorah, sets-up a manger, or dons a Krampus costume to chase naughty children through the streets, there is no question that by the end of November and into December, the ubiquitous turkey dinner becomes a mainstay of celebratory meals for the holidays. As a consumable in 2023, turkey production in the United States is — as of this writing — over 4 billion pounds of meat, 50% of which is eaten in the last two months of the year. In the United Kingdom, between nine and ten million turkeys are purchased just for the Christmas dinner alone.

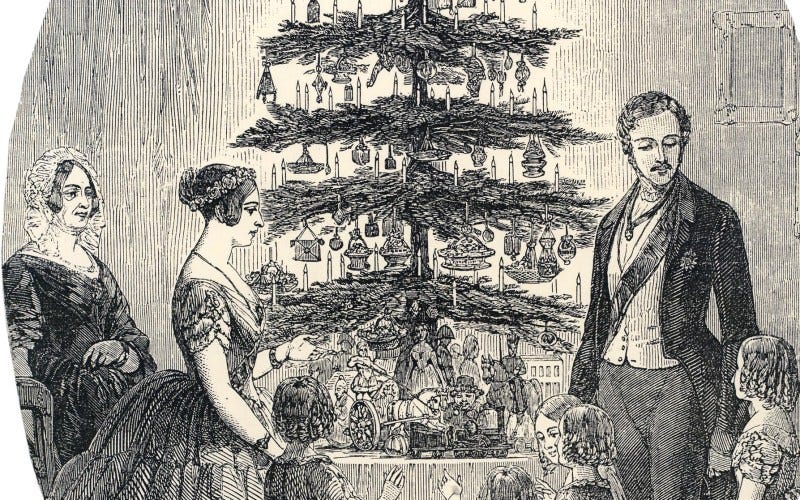

This shouldn’t be too surprising for our modern era, but during Crowley’s late 1880s Victorian childhood in the United Kingdom, the turkey had firmly established itself as the centerpiece of a holiday menu. Liturgical history aside (was it Jesus’s birth? Zoroaster? Horus?), much of the pomp and circumstance and rituals of Christmas we know today with its trees, presents, Christmas cards, carols, etcetera, come via Queen Victoria’s husband, Albert. Before 1840, Christmas and its festivities were barely mentioned in the national British press, but the 1848 the Illustrated London News, documenting the Queen and her family’s celebration saw a sudden uptick with the middle classes emulating the royals. Christmas cards were being sent, trees started coming into homes, and elaborate, celebratory meals brought families together.

Turkey, a North American bird by origin, had been brought to England in the 1550s by William Strickland, and the first artistic depiction of turkey in Europe is “a turkey-cock in his pride proper” which Strickland added to his coat-of-arms.

It is no surprise that the bird began to be included in Catholic feast days throughout early Tudor England (yes, we all mentally see Henry VIII holding a turkey leg, don’t we?), but those feasts also included boars, swans, peacocks, and beef. The sixteenth century saw a rise in turkey popularity as eastern England and Norfolk was recognized as prime real estate for their cultivation, with the Norfolk Black considered the oldest breed in the United Kingdom.

To dissuade your mental image of the classically roasted bird with its shimmering, golden skin, Georgian era cookbooks — namely, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Simple by Hannah Glasse — provides one of the earliest examples of Turducken, which Ms. Glasse referred to as “Christmas Pye.” First you put a pigeon in a partridge, then the partridge in a chicken, the chicken in a goose, and then the goose in a turkey. All of that would be encased in a pie crust with the addition of meats from rabbits and “any wild-fowl you can get” (woodcock, thrush, moor fowl, etc.).

So was it Queen Victoria and Albert who made turkey so popular in Victorian Britain? Maybe a little bit, but it was really Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol who nailed the fact that turkey was an extravagance, even for the well-to-do, and that most families sufficed with goose as Bob Crachit extolls:

There never was such a goose. Bob said he didn’t believe there ever was such a goose cooked. Its tenderness and flavour, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family; indeed, as Mrs Cratchit said with great delight (surveying one small atom of a bone upon the dish), they hadn’t ate it all at last! Yet everyone had had enough, and the youngest Cratchits in particular, were steeped in sage and onion to the eyebrows!

As I learned from the Museum of English Rural Life at the University of Reading, “both turkey and geese incurred significant costs for consumers. Before the development and improvement of the railways, most birds sold for consumption in cities had to be walked from farm to town. The birds’ feet would be wrapped in rags or covered in a painless solution of tar that acted as a little shoe to protect their feet. These journeys would have taken days and required accommodation, a team of human companions, and food, which all significantly added to cost.” Scrooge gifting the Cratchits a turkey was really a very generous offer.

What does Aleister Crowley have to say about turkey? Early in Confessions (p. 42 of the 1979 Penguin paperback), he delves into the ubiquitous Christmas turkey dinner, sometime around his 10th birthday, give-or-take:

Readers of Father and Son will remember the incident of the Christmas turkey, secretly brought by Mr. Gosse’s servants and thrown into the dustbin by him in the spirit of Moses destroying the golden calf. For the Brethren rightly held Christmas to be a pagan festival. They sent no Christmas cards and destroyed any that might be sent to them by thoughtless or blaspheming ‘goats’. Not to disappoint Alick, who liked turkey, the family had that bird for lunch on the 24th and 26th of December. The idea was to ‘avoid even the appearance of evil’; there was nothing actually wrong in eating turkey on Christmas Day; for pagan idols are merely wood and stone — the work of men’s hands. But one must not let others suppose that one is complying with heathen customs.

Crowley seems to be justifying his appreciation for turkey and including a religious reference to its consumption with the anecdote taken from Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son: A Study of Two Temperaments. This book was an autobiographical account of Gosse’s tumultuous relationship with his own father, Philip, both of whom belonged to and were active in the Plymouth Brethren sect to which Crowley’s family also belonged. Curious about “the [turkey] incident” which Crowley assumes his readers “will remember,” I sought out the original text, hoping to gain insight into Crowley’s frame of reference, for at some point in his own life — presumably as an adult — Crowley did research into the very cult which he later rejected. Interestingly, what Crowley remembers and refers to from Gosse’s account doesn’t involve a turkey whatsoever, but a pudding:

On Christmas Day of this year 1857 our villa saw a very unusual sight. My Father had given strictest charge that no difference whatever was to be made in our meals on that day; the dinner was to be neither more copious than usual nor less so. He was obeyed, but the servants, secretly rebellious, made a small plum-pudding for themselves. (I discovered afterwards, with pain, that Miss Marks received a slice of it in her boudoir.) Early in the afternoon, the maids,— of whom we were now advanced to keeping two,—kindly remarked that 'the poor dear child ought to have a bit, anyhow', and wheedled me into the kitchen, where I ate a slice of plum-pudding. Shortly I began to feel that pain inside which in my frail state was inevitable, and my conscience smote me violently. At length I could bear my spiritual anguish no longer, and bursting into the study I called out: 'Oh! Papa, Papa, I have eaten of flesh offered to idols!' It took some time, between my sobs, to explain what had happened. Then my Father sternly said: 'Where is the accursed thing?' I explained that as much as was left of it was still on the kitchen table. He took me by the hand, and ran with me into the midst of the startled servants, seized what remained of the pudding, and with the plate in one hand and me still tight in the other, ran until we reached the dust-heap, when he flung the idolatrous confectionery on to the middle of the ashes, and then raked it deep down into the mass. The suddenness, the violence, the velocity of this extraordinary act made an impression on my memory which nothing will ever efface.

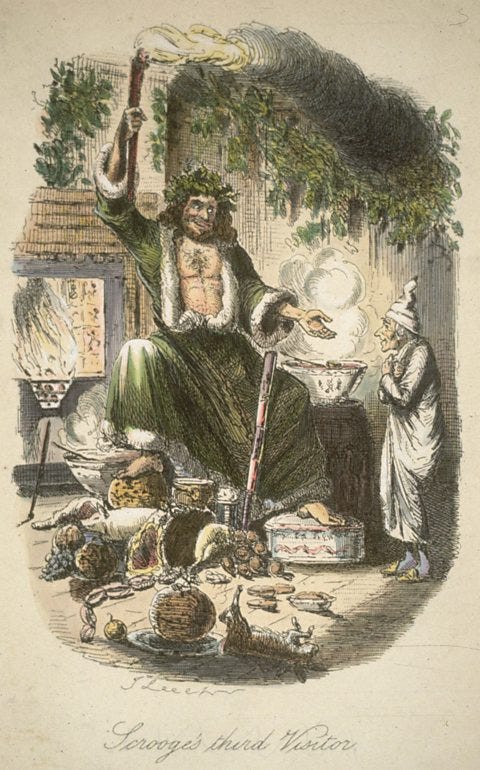

One can only wonder why Crowley felt the need to reach into the zealotry of his childhood’s religious upbringing and embellish it (or alter the story), just to validate his fondness of turkey. There is no doubt in my mind that Crowley would have read Dickens’ novella, and within it digested the distinct depiction of Victorian societal hierarchy, as portrayed in four, specific food scenes:

Ghost of Christmas Past - Scrooge witnesses his life as an apprentice and experiences the unpretentious celebration offered by Old Fezziwig.

Ghost of Christmas Present - A mighty Oak King of a figure, sitting atop a throne of gourmet largesse; from feathered game, to a barrel of oysters, Twelfth Night cakes and pies, and imported oranges (quite a luxury!)

Bob Cachet’s Meagre Dinner - A gaunt goose with mashed potatoes, applesauce (remember, that had to be “eked out”), and a flaming plum pudding that Mrs. Crachit almost doesn’t get to taste her self.

The Final, Unwritten Meal - Scrooge’s turkey has arrived at the Crachit house, so readers are left to imagine how this newly-created sumptuous feast would have been presented (I will presume it involved frogs and pigs, along with the turkey).

The collective mindset of Victorian Britain, therefore, creates an ideal Christmas feast involving a turkey. Whether or not young Alick recognizes that fact, I’m confident that in spite of the religious dogma in which he was raised, his upper-middle class family had the means to prepare and serve a luxurious meal. Perhaps he recollects enjoying it that much more due to the symbolism of the turkey as it was steeped in “pagan idolatry” and “heathen customs” and that he actually wasn’t allowed to consume it on Christmas Day proper.

Happy Holidays to you, from me. God bless us, everyone.