London - 1908

"Temperance - A Tract for the Times" and Fish Sauce

In 1908, Aleister Crowley wrote a little booklet, Temperance — A Tract for the Times, which consisted of four comic poems to various peoples in his life at that time. Thought to be privately circulated, it may very well have been that only singular presentation copies were made, for in 1939, the O.T.O officially published a limited edition of 100 that was expanded to include a fifth poem to Lady Frieda Harris, The Artist, painter and collaborator with Crowley on the Thoth tarot deck. The original four poems, however were:

Robert Winthrop Chanler: In Memoriam. An American artist known for decorative screens, acclaimed for his work in the famous 1913 Armory Show in New York, and was a well-known socialite.

Deirdre Patricia McAlpine: Hymn to Astarte. Mother of Aleister’s fifth(?)* child, Aleister Ataturk. *The jury is out as to whether Ataturk was of Crowley’s loins or not. Crowley believed he was the father, but actual parentage has never been proven and is often questioned.

“Margot,” Happy Dust: This is oddly speculative there was a woman named “Marguerite Ferrier” occasionally mentioned and is noted in Martin Booth’s A Magick Life, but Crowley had a tendency to use “Margo” as a pseudonym for whichever woman with whom he was currently sleeping.

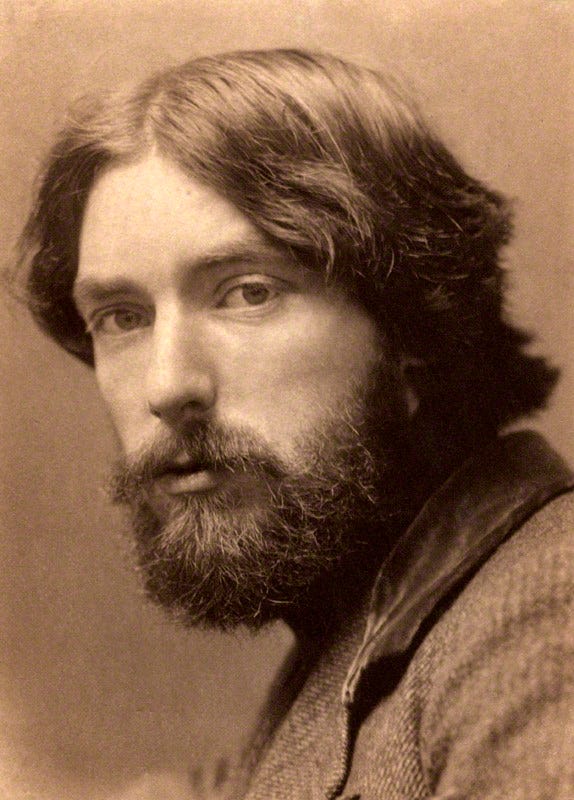

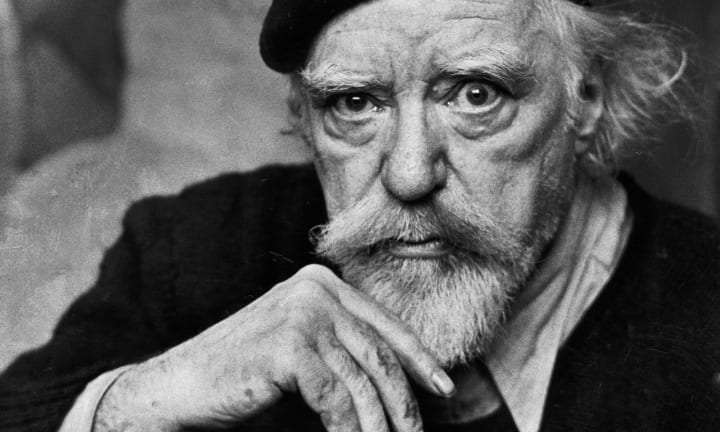

Augustus Edwin John, The Moralist: To me, Augustus John is the most interesting of the bunch. A Welsh-born artist, he was considered a prodigy and was inspired by Post-Impressionism.

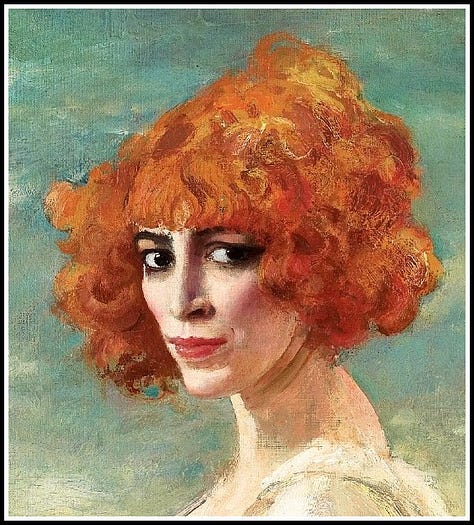

John was most famous as a portraitist; Virginia Woolf even praised him as the next John Singer Sargent. Artist extraordinaire aside, Augustus and Aleister were cut from the same Bohemian cloth. Both were charismatic and flamboyant, relished their unconventional lifestyles, appeared in ostentatious, colorful clothing, maintained multiple sexual relationships simultaneously, and sired numerous children, all from different mothers. They likely met around 1907 via mutual acquaintances in London’s art and literary circles, and I have no doubt that Crowley’s own attempts at portraiture were inspired by those done by John. Consider the multiple portraits of the Marchesa Casati:

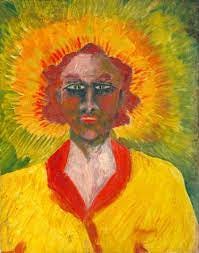

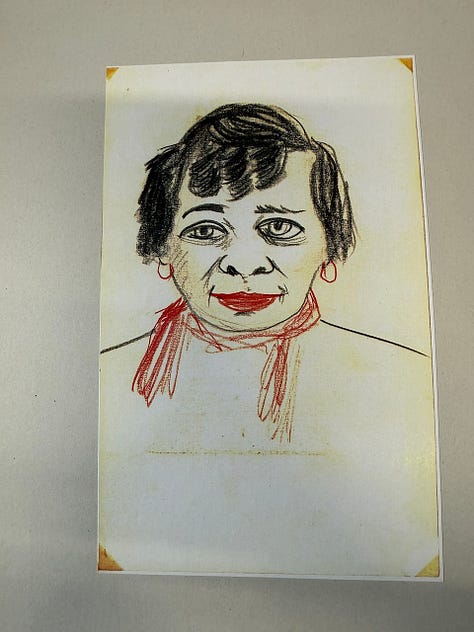

Crowley’s attempts of some of his Scarlet Women:

Of course, John, being formally trained — first at the Tenby School of Art in Wales as a teenager, then later at the Slade School of Art, UCL, in London — was the more accomplished artist, with bold, assured brushstrokes and classic, composed frontal postures. John was known for presenting penetrating psychological insight with his portraits, something Crowley would undoubtedly aspire toward in spite of his naïveté. Both exude confidence by having their subjects peer directly at the viewer, while Crowley’s exaggerated stares present a more unsettling energy.

All that artsy stuff aside (this is about food, after all), let’s take a look at Crowley’s poem, “The Moralist,” written for Augustus John. Before the ten six-line stanzas written in iambic tetrameter, there is the dedication swiped from Baudelaire; in French, “Il faut être toujours saoul,” which translates to “One must always be drunk;” a philosophy of living to which both gentlemen frequently applied themselves, if not through alcohol, then some other libation. The poem in full:

Delaying to do the thing that's right

Is as bad as having a funk on;

Then why should we wait till Saturday night

To get all kinds of a drunk on?

With brandy a century old in sight,

Why should we wait till Saturday night?If I haven't a house on the Grand Parade,

I'll build me a hut of wattle.

The corkscrew seems to have got mislaid?

Then smash the neck of the bottle!

Courage and will and a whack will aid,

Though the corkscrew seems to have got mislaid.Anatomists say that a single wing

Isn't much for a bird to fly on.

There's not much ginger about the spring

Of the fiercest one-legged lion.

Another bottle's the obvious thing

To get the ginger into our spring.Beloved brethren, listen to me!

If there's one truth of divinity

Clear, it's the virtue there is in Three,

And I myself was at Trinity.

The least we can do is to seek and see

The virtues hid in the Number Three.If much be good, then better is more,

As any logician will prove you;

It's only a step from Three to Four;

May the argument's lever move you!

It's simply illogical not to explore

The little bit on from Three to Four.On bread alone though a man can't thrive,

Saint Luke says nothing of brandy;

It may be the thing to keep us alive,

And I see there's a bottle handy.

Open it, Bill! That's only Five.

It may be the thing to keep us alive.The Road of Excess, said William Blake,

To the Palace of Wisdom leads one;

Open a bottle for Wisdom's sake!

And I am the boy that needs one.

It's a long, long way, but it's good to take

Open a bottle for Mishter Blake!At the door of Burgess' Fish Sauce Shop

She stood, oh, how does it go, boys?

Well, "truly rural" will do for the cop,

If you say it quiet and slow, boys.

Why the devil should anyone stop,

When "truly rural" will do for the cop?I d'know 'f 't struck you, i' shtruck me

Th'was somethin' wrong with the pheasant.

Say, how would a little drink, maybe --

You'know, 'void an'thing 'npleasant?

Say, doctor, d'you preschribe it, shee?

W'd'y' think, lil drink, maybe?'Fence o' th' Realm Act, I'm no fool,

All tha', Tha's ri', damnation!

'Member, 'n I wazza boy a' school,

A-Thanks, Ol' top, jus' trench ration

Zhero -- overra top'sh my rule

'Member, 'n I wazza boy a' school --

As for the poem itself, when read aloud, it is easy to hear a descent from spry aphorisms to the slurred speech of a drunkard—exactly what Augustus was known to be. Actual words degrade into tipsy gibberish, causing the reader to become inebriated by its very words, through its consumption. By beginning with the Baudelaire line, the emphasis on intoxication is almost a command more than an entreaty. Crowley also embodies the poem with contemporary erudition in references to William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (“The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom”), but also to the headquarters of a well-known food brand, “Burgess’ Fish Sauce Shop:”

At the door of the Burgess’ Fish Sauce Shop

She stood, oh, how does it go, boys?

Well, “truly rural” will do for the cop,

If you say it quiet and slow, boys.

Why the devil should anyone stop,

When “truly rural” will do for the cop?

In spite of the many brandy references and what must have been a much loved pheasant entrée within the poem, it is the Burgess mention which piqued my interest.

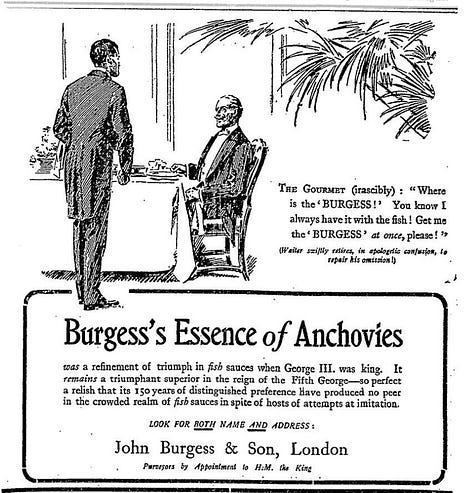

Introduced in 1775, Burgess’ Essence of Anchovies became the first sauce of any kind to enjoy a brand name and earn nationwide acclaim. Crafted from crushed anchovies and “secret” spices, the concoction was gently heated in water, strained, and bottled. Its fame was wide and varied; from being part of the necessary provisions aboard HMS Victory in 1805 (Lord Horatio Nelson’s ship), loved by both Lord Byron and Sir Walter Scott, the brand earned awards at the 1867 Paris Exhibition and 1873 London International Exhibition, and had the honor of being appointed Purveyor to King George V in 1911. Along with the sauce, the Burgess Fish Sauce Shop would have also sold containers of anchovy paste.

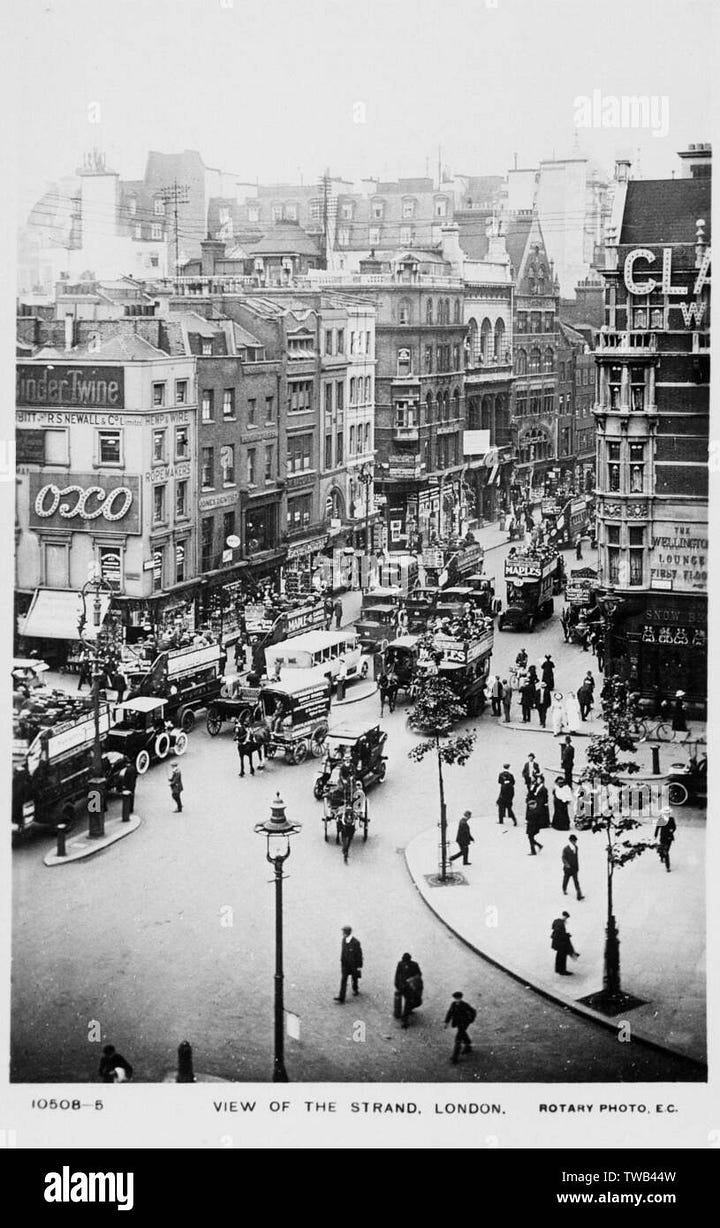

For most of you, if you look at the standard condiments in your pantry or refrigerator, you are likely to see mustard, ketchup, and mayonnaise. Possibly soy sauce. Americans probably have a barbecue sauce bottle or two, some godawful Ranch dressing, A-1 steak sauce, while the Brits have HP Sauce, malt vinegar, and a chutney for the curries. From the late Georgian period and well into the Edwardian era, an anchovy essence was a must-have in middle- and upper-class kitchens. Both cookbook mavens Hannah Glasse and Mrs. Beeton used it frequently in recipes for gravies, meat sauces, and soups. When asked to describe its taste, it is often equated to the modern Thai fish sauce, nam pla (น้ำปลา), but I believe the British fish sauce to be a bit thicker and richer, similar to an ancient Roman garum, also a fermented fish sauce. Invoking the image of where Crowley had the earthy and probably pungent “she,” standing and heckling “truly rural,” these shots below are where the action would be taking place; in front of the Burgess store which existed on The Strand, where the fish sauce possibly relates to the earthy and pungent woman involved in the scene.

It is more than just a fish sauce; it is also an anchovy paste (pictured above on the right), also created by Burgess. Sold in ceramic pots, sometimes decanted into small lidded silver or glass dishes, often with a tiny serving spoon or butter knife, the paste, known as Gentleman’s Relish. was a morning staple at any formal breakfast, luncheon, or light supper, especially in gentlemen’s clubs, hotels, or during a country house weekend. Considered a breakfast delicacy, the gentleman would grasp a warm slice of toast that had been prepared for him by his manservant, first spread a thin layer of fresh butter, and then with a clean knife or spoon, smear a dollop of the paste—being careful not to overwhelm his fellow diners with too big a serving, as the aroma and flavors were both robust and salty. This would have been a staple of Crowley’s youth as well as for any strapping young gentleman of the Edwardian era.

What emerges from Temperance — A Tract for the Times is a vivid tableau of Edwardian eccentricity, filtered through Crowley’s singular wit and the larger-than-life characters who populated his orbit. Each poem is both an affectionate caricature and a subtle exposé, laying bare the artistic, sexual, and gustatory appetites that fueled this circle of artists, muses, and misfits. The mention of Burgess’ Fish Sauce Shop is more than a passing culinary reference; it is a portal into the era’s gustatory landscape, a reminder that even the most esoteric literary salons were shaped by the condiments and customs of their day. In celebrating intoxication, excess, and conviviality, be it through brandy, sex, or the humble anchovy paste, Crowley draws a line of continuity from the boozy salons of Paris to the well-provisioned London pantries. Ultimately, “The Moralist” is less a didactic tract than a riotous homage to the pleasures of the table, the brush, and the bottle—a fitting tribute to Augustus John, and to a vanished world where art and appetite were inseparable.