London, October 1928

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese -- Pudding, Part I

An American will read pudding and immediately think of the horrific Bill Cosby-peddled cups of sweet gelatinous goo under the brand name Jell-O® that came in “chocolate” or “vanilla.” Akin to a custard, this form of “pudding” was based off a custard made of eggs and flour that first came to life in print around 1730. Due to its creamy texture, pudding of this sort was considered proper calorie-rich food to give to invalids or children, only being bastardized into the powdery, instant-mix concoctions of the mid-20th century.

If you are British, you bloody well know that pudding is part of the culinary heritage of Albion. Now pudding is a catch-all term for the sweet bit at the end of a meal; be it cake or biscuit (cookies, for the Yanks), galette or pie. Historically however, pudding is very ancient. From the Latin word botellus (sausage), it segued into the French, boudin. Alternatively, the West Germanic pud (which means “to swell”), the Westphalian puddek (“lump”), or the Low German, puddle-wurst which is their version of black pudding (blood sausage). From Regula Ysewijn’s brilliant Pride and Pudding - The History of British Puddings, Savoury and Sweet, we learn essentially, pudding is the name of any mixture that is encased in animal skins (haggis or sausage), cloth, pastry, or a mould. A pudding is a form of homonym for being either the dessert at the end of a meal or pasty custard, an accompaniment — like Yorkshire pudding or a pop-over — or a pastry-encased stew; what Americans would call a pot-pie.

Located at 145 Fleet Street on Wine Office Court, the pub then known as “The Horn” had been situated at that location since 1538. Sadly, the Great Fire of 1666 decimated this neighborhood along with the other 80% of London, but a new establishment was quickly rebuilt in the same place, with some of the vaulted cellars believed to have come from a 13th century Carmelite monastery which also occupied the site. Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese (hereafter referred to as “The Cheese”). The entrance is down a narrow alley and once you step inside its smoke-laden, dark wood interior, it feels slightly oppressive, as the ceilings are low, the air is thick, and history can be felt in your bones as portraits of Dr. Samuel Johnson festoon the walls.

From Edward Spencer’s Cakes and Ale: a dissertation of banquets, interspersed with various recipes, more or less original, and anecdotes, mainly veracious (4th ed.; London, 1913)

A little way up a gloomy court on the north side of Fleet Street – a neighbourhood which reeks of printers' ink, bookmakers' "runners," tipsters, habitual borrowers of small pieces of silver, and that "warm" smell of burning paste and molten lead which indicates the "foundry" in a printing works - is situated this ancient hostelry. It is claimed for the "Cheese" that it was the tavern most frequented by Johnson, in his Fifty Years' Recollections Literary and Personal, published in 1858, says: "I often dined at the “Cheshire Cheese.”

[The pudding] which is served on Wednesdays and Saturdays, at 1:30 and 6:00, is a formidable-looking object, and its savour reaches even into the uttermost parts of Great Grub Street. As large, more or less, as the dome of St. Paul's, that pudding is stuffed with steak, kidney, oysters, mushrooms, and larks. The irreverent call these last named sparrows, but we know better. This pudding takes (on dit) 17 ½ hours in the boiling, and the "bottom crust" would have delighted the hearts of Johnson, Boswell, and Co., in whose days the savoury dish was not. The writer once witnessed a catastrophe at the "Cheshire Cheese," compared to which the burning of Moscow or the bombardment of Alexandria were mere trifles. 1.30 on Saturday afternoon had arrived, and the oaken benches in the refectory were filled to repletion with expectant pudding-eaters. Burgesses of the City of London were there - good, "warm," round-bellied men, with ploughboys' appetites - and journalists, and advertising agents, and "resting " actors, and magistrates' clerks, and barristers from the Temple, and well-to-do tradesmen. Sherry and gin and bitters and other adventitious aids (?) to appetite had been done justice to, and the arrival of the "procession" - it takes three men and a boy to carry the pièce de resistance from the kitchen to the dining-room - was anxiously awaited. And then, of a sudden we heard a loud crash ! followed by a feminine shriek, and an unwhispered Saxon oath. "Tom" the waiter had slipped, released his hold, and the pudding had fallen downstairs! It was a sight ever to be remembered - steak, larks, oysters, "delicious gravy," running in a torrent into Wine Office Court. The expectant diners (many of them lunchers) stood up and gazed upon the wreck of their hopes, and then filed, silently and sadly, outside. Such a catastrophe had not been known in Brainland since the Great Fire.

This is important pudding, folks. Crowley, a product of classic British society norms, attending boarding school from the age of eight, where pudding was a regular feature of school life. Economical, relatively easy to make with ingredients of flour, suet, meat (for savory) or fruit (for sweet), pudding provided a familiar and comforting way to provide essential calories and hearkened to the security of home.

When planning my January research trip to London, I used Phil Baker’s City of the Beast – The London of Aleister Crowley book to schedule where I should have my meals to mirror Crowley’s hangouts, but I also always try to also dine at the oldest restaurants in a particular city, so this killed two birds with one stone. Of course I ordered the pudding, which I seriously doubt was historically served on lentils with a micro greens garnish:

In mid-October of 1928, Crowley was in the throes of negotiating funds from outside sources and relying on Gerald Yorke to manage accounts. From this transcript that Gerald typed from Crowley’s letter, we have our first mention of pudding: “To confirm my wire [money transfer] of 2 P.M. ‘come this Saturday Situation improved. Bring pudding.’ Pudding connotes Cheshire Cheese, but is to be extended to include my watch if it is ready.” This makes me believe that if there is leftover funds after the purchase of the pudding, a pocket watch – probably out for repairs – is ready to be retrieved.

To justify the expense: “The pudding may be regarded as a business investment. I am going to arrange a luncheon party for the lady of the well (Mrs. Fremman) to discuss the aforesaid pudding. I think her husband will be back by that time, so that any considerations of propriety will be met in a manner exquisitely satisfactory to our finer feelings.”

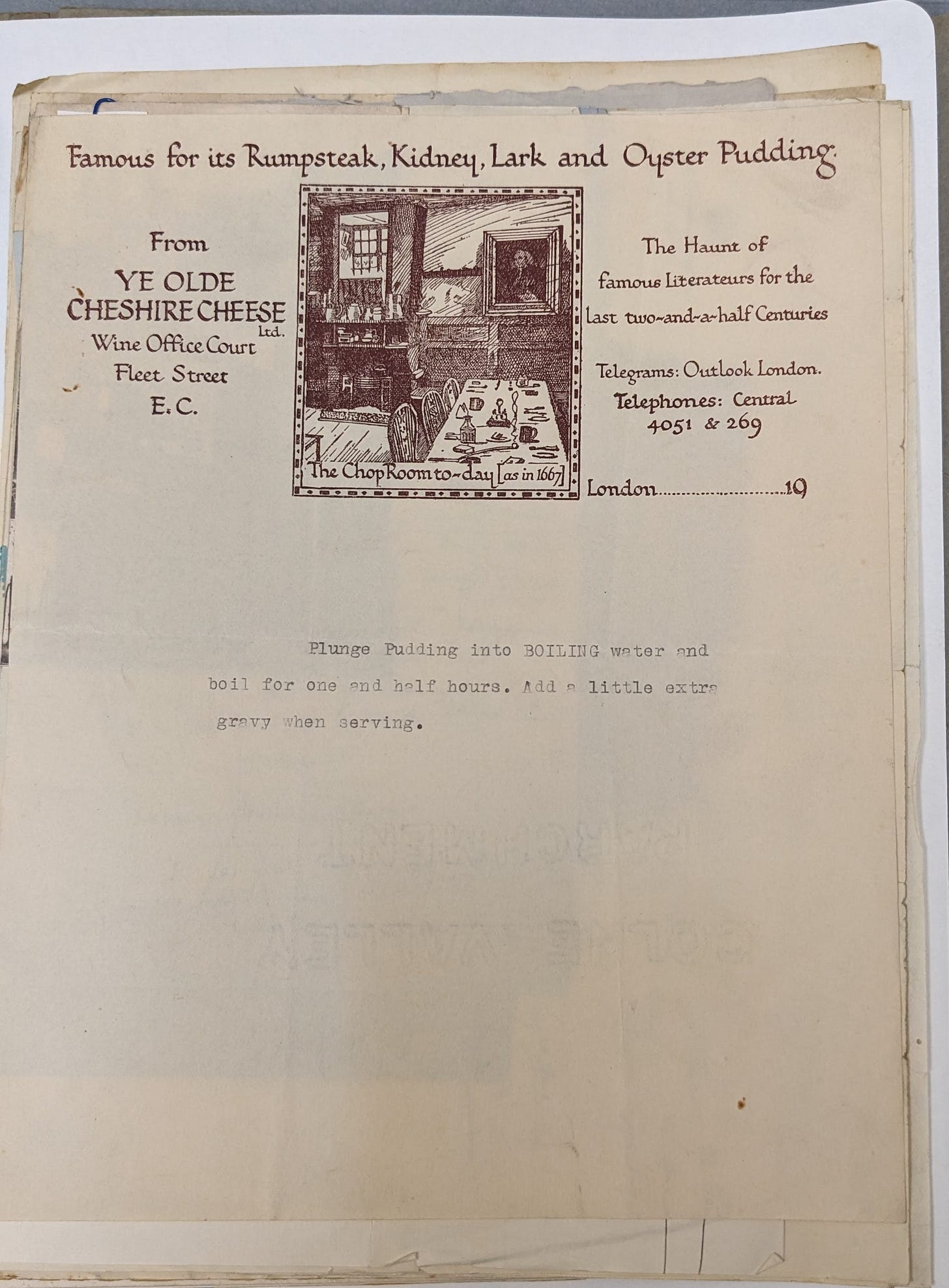

And the piece de resistance for yours truly as researcher? Discovered amongst the Aleister Crowley archive of personal papers at the Warburg Institute is the very page from Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, with instructions on home preparation:

Wait, why is this Substack entry Part I, you ask?

Because in a few days, I’ll be posting the recipe for the famous Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese rumpsteak, kidney, lark, and oyster pudding (in suet crust), that’s why! Stay tuned….