London Research Report, Day 1, Part 1

Absinthe at the Café Royal

When I first set out to plan a London research trip, I had two objectives in mind: reading and eating. From the Warburg Institute, I would be spending upwards of eight hours a day, reading and documenting as many culinary references in the unpublished Crowley archives as possible. Sadly, I did not realize until I was handed my first box of letters, ephemera, and diaries, that to read everything would be a two- to three-month task, at the minimum. I seem to have a superpower of spying food words within paragraphs of text, so I scanned as much as I could, as quickly as I could, and ended up photographing hundreds of entries to reference and research later. Some delightfully hidden gems were uncovered that will be shared in the coming weeks.

My other objective was to eat at as many restaurants as possible that may have been frequented by Crowley. Initially, the historian in me worked at creating a listing of the oldest extant London eating establishments from the late Victorian era through World War II. One of the great joys of the United Kingdom in general is the fact that there are pubs – or public houses, as they were known – still operating from the 900s. (The Porch House in Stow-on-the-Wold, located in Gloucestershire, is reputed to have been founded by the Saxon Duke of Cornwall, Athelmar, in 947 A.D., and was subsequently run by the Knights Hospitallers.) Then I stumbled upon Phil Baker’s excellent book, City of the Beast: The London of Aleister Crowley which proved invaluable to me in confirming many of the eateries that I planned to visit, but also providing new intel for me to explore.

Initially, for my eight days, the plan was to have a very minimal breakfast – tea and a piece of toast, or bit of fruit, at the most – to save myself for lunch and dinner. I reasoned that on the day of my arrival, at 11:00 in the morning on a Saturday after twelve-plus hours of traveling, I could start with a quick stop at a pub for lunch, a little wandering and exploration, and rebuild my appetite), and be ready for another meal come dinnertime. While airline food is almost always forgettable, there is an exception with Virgin Airlines and their boxed cream tea offering; complete with finger sandwiches, warm scone with jam and clotted cream, and tart. As this was served an hour before landing, destroying my plan for a pub lunch as I was quite full to the extent that after landing and checking into the favored old Tavistock Hotel (where many OTO brethren have stayed, and which is barely a block-and-a-half away from the University of London where the Warburg Institute is housed), I just wasn’t hungry enough to risk ruining my evening meal.

Not knowing if any of the desired restaurants were difficult to get into or not, I had worked hard the week before the trip to secure reservations at as many places as possible. Within those first twenty-four hours in London after a single meal, I realized I longer had the eating stamina or capacity of my youth (or of a certain, beloved Norseman many of us know whose gargantuan dining adventures are the stuff of legends), and the week unfolded with me sufficing on a single meal a day. Sometimes not even that much.

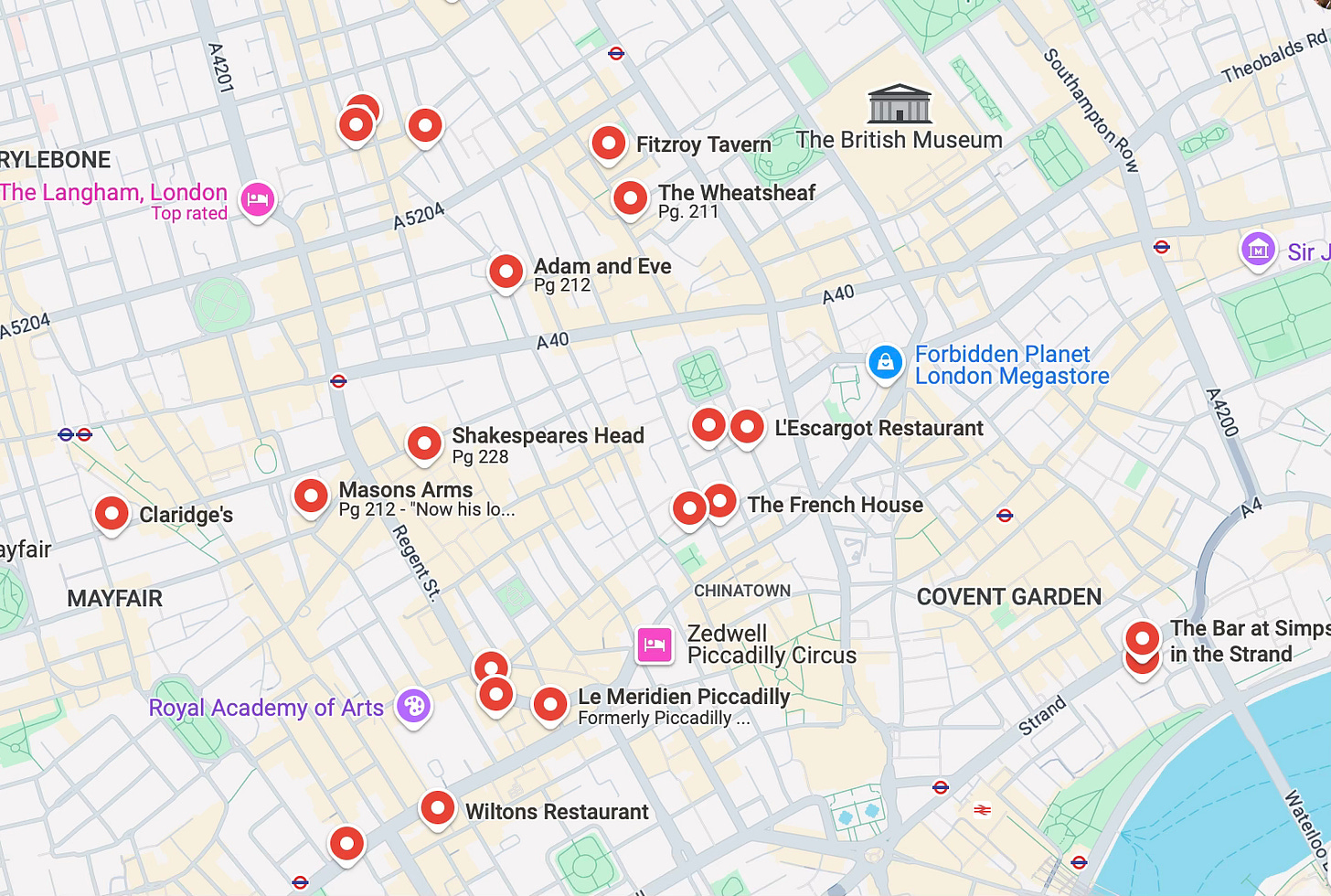

Besides its tremendous affordability, the Tavistock Hotel also has the advantage of its proximity to Crowley’s personal neighborhoods, that of Piccadilly and Soho. Using a mapping software, I placed virtual pins in the restaurants and pubs talked about in the Baker book and soon realized that the bulk of them were less than a mile’s walk from where I was situated. Even with a charged-up Oyster card in hand, I relied very little on the tube and walked most everywhere for the next eight days.

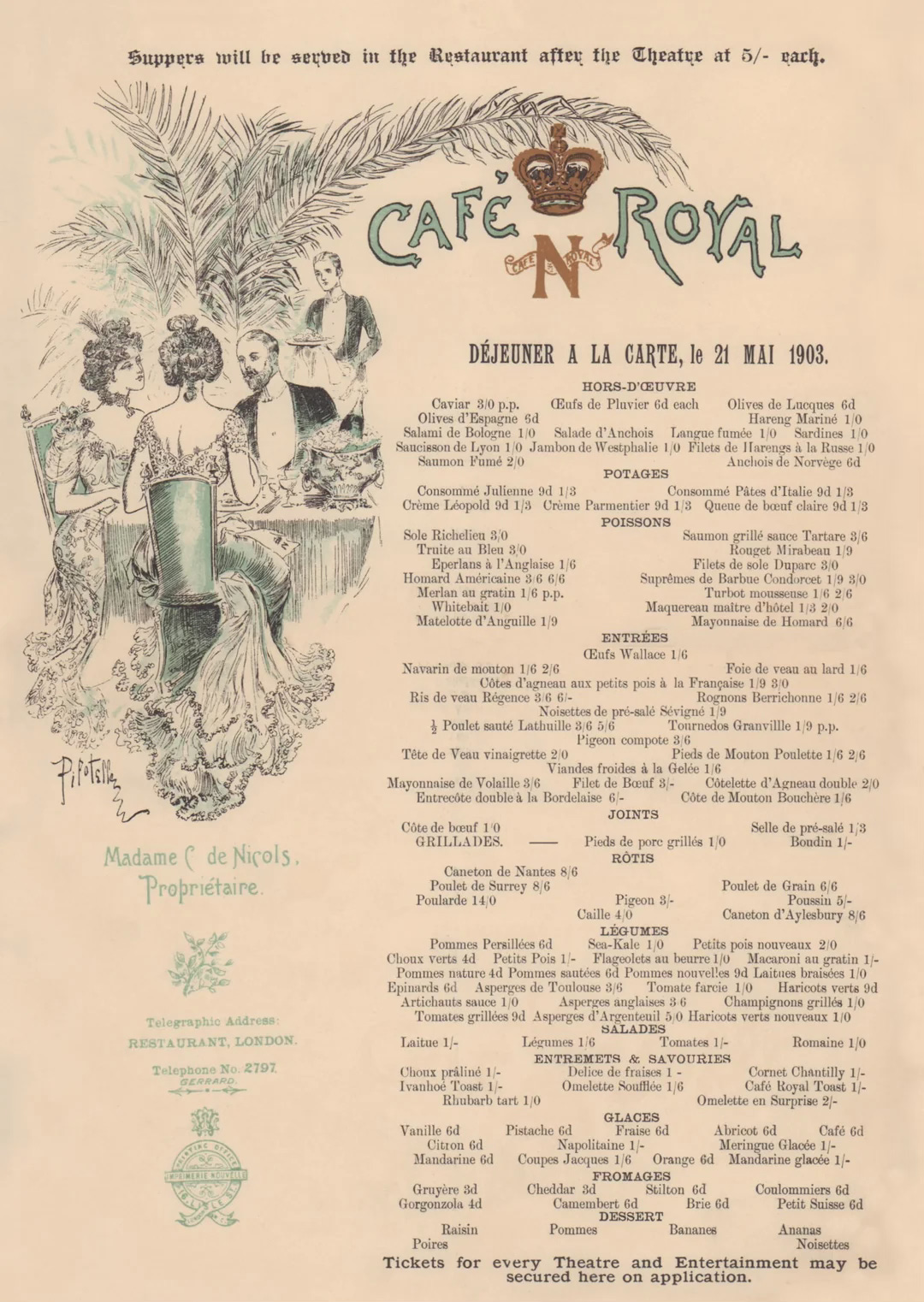

My first night’s dinner reservation was at Bentley’s in Piccadilly (the next entry), and as I was nearing its location with still an hour to kill, I spied on Regent Street another important establishment, The Café Royal. In 1865, French wine merchant Daniel Nicholas Thévenon (who shortened his name to just Daniel Nicols) and his wife, Célestine opened the restaurant, which quickly thrived, becoming one of the most prominent establishments “to see and be seen.”

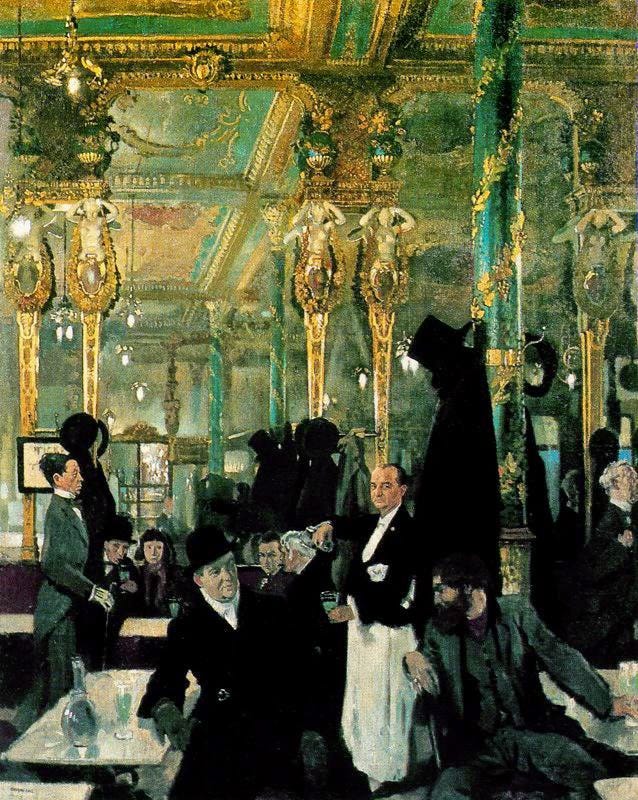

During this Belle Époque, Café Royal’s wine cellar was one of the greatest in the world. The interior was the epitome of opulence, with ceiling murals surrounded by gilded Rococo frames, mirrors that reflect golden faux pillars on the walls, and rich leather seats and banquettes for literati like Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw, and Virginia Woolf who would sit and whisper amongst themselves. It was known that this is where Wilde first met the love of his life, Lord Alfred Douglas; his “Bosie.”

Crowley was a known habitué of Café Royal and my deepest regret is that the restaurant as it once stood was closed in 2008, only to be renovated and reopened in 2012 as The Hotel Café Royal. There is still a restaurant within the hotel, headed up by two Michelin-starred chef, Alex Dilling, but the food now served is what one would find at most trendy, modern, eatery “that creatively highlights seasonal, local ingredients.” (i.e., boring.) I’m here not only to dine at the historic restaurants, but to eat the same types of dishes and offerings as afforded any late Victorian/early Edwardian gentleman. Wanting just a glimpse of what once was, I stepped inside the large, glass doors and situated just off the lobby of this elegantly appointed, mostly black-and-chrome interior, was delighted to find The Green Bar, a cocktail establishment devoted to absinthe and its mystical qualities.

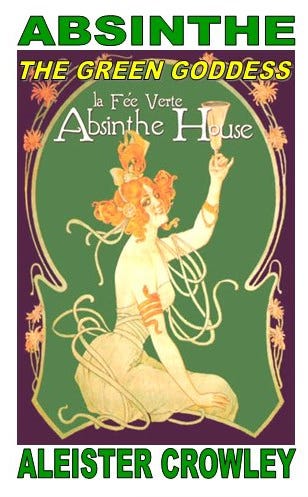

Aleister Crowley was a great imbiber of the magical liquor, and while visiting the also historic and famed New Orleans Old Absinthe House in Louisiana, drafted the following poem, published in The International in October of 1917.

La Legende de l'Absinthe

Apollon, qui pleurait le trepas d’Hyacinthe,

Ne voulait pas ceder la victoire a la mort.

Il fallait que son ame, adepte de l’essor,

Trouvat pour la beaute une alchemie plus sainte.

Donc de sa main celeste il epuise, il ereinte

Les dons les plus subtils de la divine Flore.

Leurs corps brises souspirent une exhalaison d’or

Dont il nous recueillait la goutte de — l’Absinthe!

Aux cavernes blotties, aux palis petillants,

Par un, par deux, buvez ce breuvage d’aimant!

Car c’est un sortilege, un propos de dictame,

Ce vin d’opale pale avortit la misere,

Ouvre de la beaute l’intime sanctuaire

—Ensorcelle mon coeur, extasie mort ame!Translated: The Legend of Absinthe Apollo, who mourned at Hyacinthe’s demise, Refused to concede this victory to Death. Much better that the soul, adept in transformation, Had to find a holy alchemy for beauty. Thus with his celestial hand he drained and crushed The subtlest harvest of the garden goddess, The broken bodies of the herbs yielding a golden essence From which we measure out our first drop — of Absinthe! In lowly hovels and in glittery courts, Alone, in pairs, drink up this potion of desire! For it is sorcery — as one might say — When the pale opal wine ends all misery, Opens beauty’s most intimate sanctuary — — Bewitches my heart, and exalts my soul in ecstasy!

He then wrote a love letter of sorts; an essay both extolling the virtues of this elegant drink while admonishing the looming rise of prohibitionism, Absinthe: The Green Goddess, for February 1918 edition of The International, including the original poem. Never published there, it is reported that the entire issue of the magazine was withdrawn due to World War I sedition laws as the publisher, George Sylvester Viereck, was a devout sympathizer for Germany since the war’s onset in 1914. Crowley even took over of editorial management of the magazine for several months, before an entirely new editorial team assumed control. Crowley ultimately self-published

And so I found myself in a metaphorical temple devoted to the famed beverage, and glancing over the wide selection of absinthes offered in this elegantly cozy bar, I spied Devil’s Botany London-made absinthe. Never ignoring a sign, I commenced my grand Crowley-themed London adventure by partaking in the ritual of absinthe preparation, known as the French drip method. The bartender poured the appropriate amount of absinthe in the glass, laid the flat, perforated spoon squarely atop the glass, crowning it with the compressed square of white sugar. Filling the reproduction Art Deco fountain with ice and water, it was placed squarely in line with the glass, so that I could personally dispense the desired amount of water; slightly melting the sugar and diluting the beverage, just so, as the clear liquid turned ever-so-slightly cloudy. Dipping the pointed spoon into willing receptacle, a gently stirred so the sugar would dissolve a bit more, and took my first sip…