Paris, October 1908

Magickal Retirement and the Garibaldi Biscuit

I am leaving for Paris in a few weeks and knew it was time to dive back into Crowley’s John St. John diary for its firsthand accounts of where Aleister dined during his magical retirement in October of 1908 — just before his 34th birthday. Of course, this was hardly his first or only time in Paris. Seven-year-old “Aleck” had been brought by his parents, Edward and Emily, on a family holiday in 1883. At nineteen, the budding mountaineer traveled through Paris en route to Switzerland to ascend the Eiger. He returned in earnest to formalize his magical career with the Golden Dawn in 1898 and called Paris home many times until his expulsion on Thursday, April 18, 1929. Leaving Paris was a loss that grieved him deeply, for it was the closest he would ever come to finding a true intellectual and spiritual haven.

The John St. John diary begins meticulously, noting every meal and drink, though his attention wanes as the days pass. On the very first morning: “At eight o’clock, I rose from sleep and, putting on my Robe, began a little to meditate... I rose and went out to the Café du Dôme where I took coffee and a brioche, after buying an exercise book in which to write this record.” His choice of haunt was telling. Not knowing his exact address, I surmise from his frequent visits to Le Dôme for citron pressé, oysters, or a simple steak that he lodged in or around Montparnasse or the Latin Quarter. Later that very afternoon, he shopped for provisions: “two pears, half a pound of Garibaldi biscuits, and a packet of gaufrettes.” Despite his continental air, Crowley remained deeply British as only an Englishman in Paris would stock up on Garibaldi biscuits.

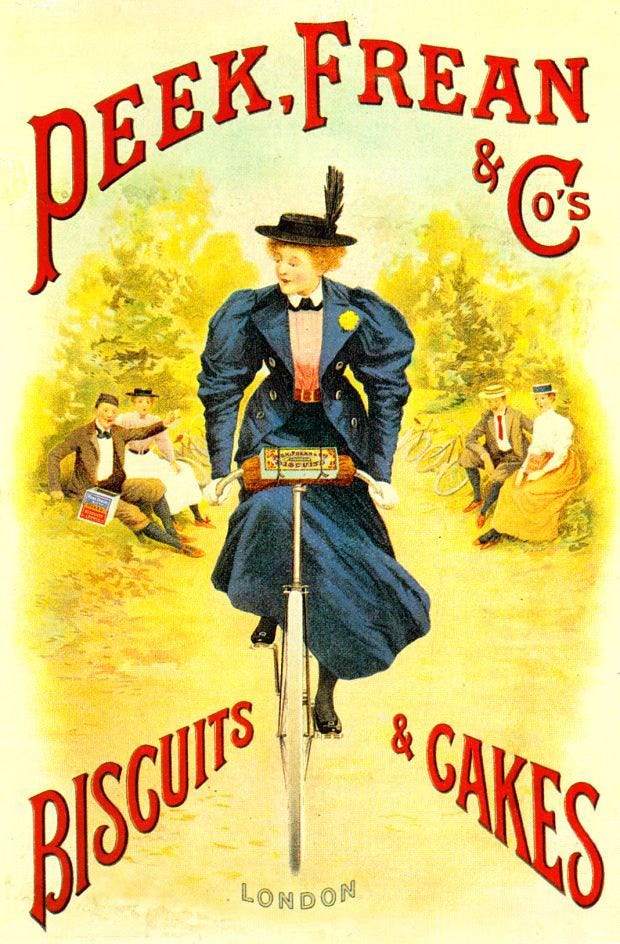

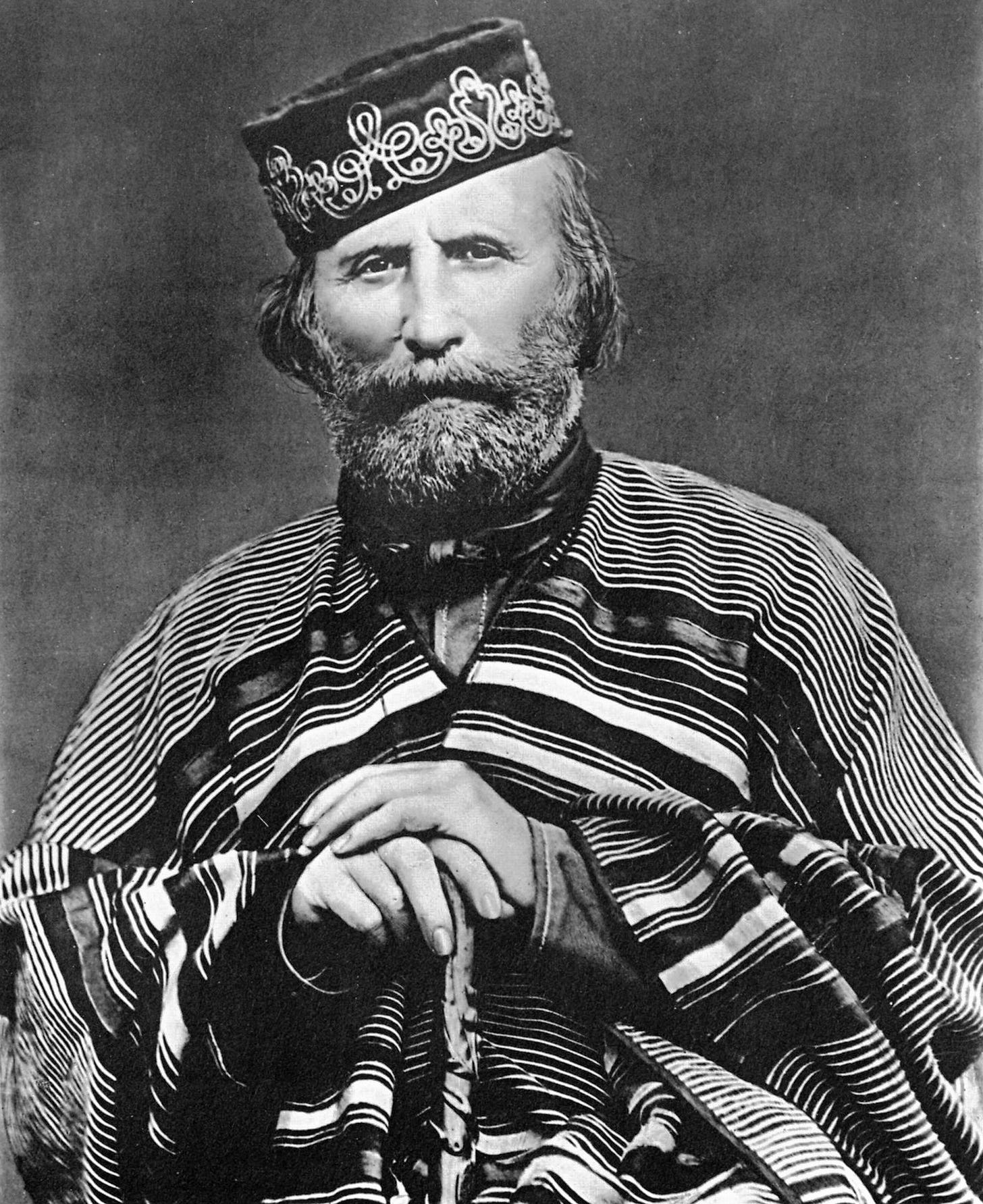

The Garibaldi was itself a Victorian invention, first baked in 1861 by Jonathan Dodgson Carr for Peek, Frean & Co. of London. Named for the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had been lionized during his 1854 visit to England, the biscuit combined celebrity marketing with industrial innovation. Several colorful legends arose to explain the name. One tale claimed Garibaldi improvised a field ration of bread soaked in berries and horse blood, inspiring the biscuit’s fruit filling. Another story linked it to a dark currant bun Garibaldi supposedly enjoyed in Sicily. In truth, the naming was likely a savvy marketing move—capitalizing on Garibaldi’s fame rather than any direct recipe from the man. (A popular myth even imagined Garibaldi accidentally sitting on a pair of biscuits during his visit, supposedly flattening them into this new form. However, there is no evidence that the general himself had anything to do with inventing the biscuit.) In essence, the Garibaldi biscuit’s development was a fusion of culinary innovation and celebrity tribute: a Victorian-era sweet created by an industrial baker and branded with the name of a contemporary hero to capture the public’s imagination.

Thin layers of dough sandwiched with currants quickly became known as “squashed fly biscuits,” a nickname beloved by generations of British schoolchildren. By the late 19th century, Garibaldis were exported across the Empire, copied in the United States as “Golden Fruit,” and folded into the everyday fabric of Victorian and Edwardian life. Though their popularity waned in the 20th century as richer biscuits took center stage, they never vanished. Today, Crawford’s continues to make them—a legacy of Peek Frean’s failure to trademark the name.

I confess to being an old fan of Garibaldis. My father ate them, and I inherited the taste. Yes, they are rather dry and chewy, but for tea or coffee I prefer a crisp biscuit—shortbread, pecan sandies, or Garibaldis—to anything too sweet. Living in California, they are hard to find; when not mail-ordering Crawford’s version, I have tried making them at home. My first attempt, with raisins instead of currants, was bland and uninspired. So I’ve adapted the recipe, adding citrus and spice to heighten their humble character. Currants usually appear around the holidays, when I’ll try again—but in the meantime, here is my spiced version, a nod both to Crowley’s Paris purchases and to a biscuit that has remained a British staple for over 150 years.

Recipe: Spiced Raisin Garibaldis

150 g / 1¼ cups currants (or raisins), roughly chopped

75 ml / ⅓ cup orange juice

75 ml / ⅓ cup Grand Marnier or Triple Sec

125 g / 1 cup self-rising flour

Pinch of salt

75 g / ⅓ cup unsalted butter, cubed and chilled

25 g / 2 tbsp caster sugar

Zest of 2 lemons (about 2 tbsp)

1 tbsp ground cardamom

1 large egg, separated

1 tbsp water

Method

Heat oven to 180°C / 160°C fan / 350°F / Gas 4. Simmer raisins with juice and liqueur for 5 minutes; drain, pat dry, and flatten under cling film with a rolling pin.

Sift flour, salt, and cardamom into a bowl. Rub in butter until crumbly, add sugar, then mix in egg yolk and water to form a dough. Wrap and chill 20 minutes.

Roll out two 20 × 15 cm (8” × 6” in) rectangles. Brush one with egg white, layer with fruit, then top with the second sheet.

Roll gently into a 25 × 20 cm (10” × 8” in) rectangle. Trim edges, cut into 6–12 biscuits, prick with a fork, and brush with egg white.

Bake on parchment-lined sheet for 12–15 minutes, until golden. Cool briefly, then transfer to a wire rack.

Sidebar: Biscuits Abroad

Crowley’s purchase of Garibaldi biscuits in Paris fits a broader pattern among Britons abroad. From the 19th century onward, English travelers often sought out familiar foods — whether Huntley & Palmers tins, Bovril, or cups of strong black tea — as anchors of home in foreign cities. Imported biscuits in particular carried comfort and identity: to unwrap a packet of Garibaldis in Montparnasse was to reaffirm one’s Britishness even amid the cafés of Paris. For Crowley, ever the cosmopolitan yet rooted in English tastes, that half-pound of currant biscuits symbolized not just sustenance but continuity—proof that even in exile, the flavors of Britain could still be summoned at will.

Hmmmm… Wonder if these are actual currants? https://a.co/d/e9BtUVZ

I'm in the small number who rather miss Golden Fruit biscuits. Also in rather a snit that dried currants are small raisins rather than actual dried currants.