San Francisco - 1901, Chinatown

Chinatown; Opium and Chop Suey

When last we saw our wayward hero in late April 1901, he arrived in San Francisco and had checked into the famed Palace Hotel. As opulently elegant and inviting the Palace was — and still is — we know from Crowley himself he spent very little time in the hotel and was seemingly little impressed with what the city had to offer, save its Chinatown (from Confessions):

It [San Francisco] was a glorified El Paso, a madhouse of frenzied money-making and frenzied pleasure-seeking, with none of the corners chipped off. It is beautifully situated and the air reminds one curiously of Edinburgh. At the time it possessed a real interest and glory — its Chinatown. During the week I was there, I spent most of my time in that quarter. It was the first time I had come into contact with the Chinese spirit in bulk; and, though these exiles were naturally the least attractive specimens of the race, I realized instantly their spiritual superiority to the Anglo-Saxon, and my own deep-seated affinity to their point of view. The Chinaman is not obsessed by the delusion that the profits and pleasures of life are really valuable. He gets all the more out of them because he knows their worthlessness, and is consequently immune from the disappointment which inevitably embitters those who seek to lay up treasure on earth.

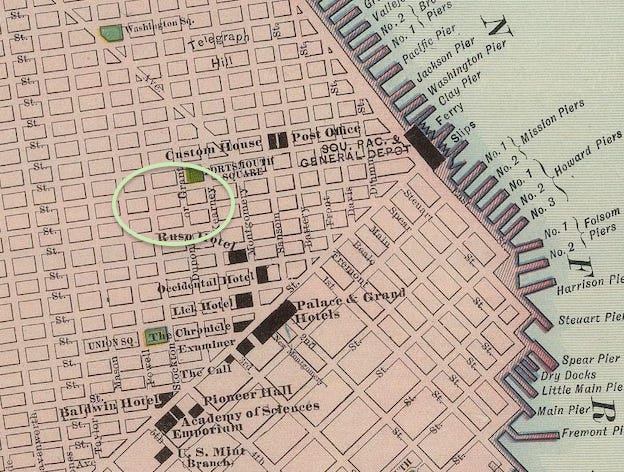

He goes on the say, “California got on my nerves. Life in all its forms grew rank and gross, without a touch of subtlety.” Be that as it may, these were written twenty-five years later; even his second visit in 1915, so these jaded thoughts may have had something to do with the latter excursion, or simply the passage of time had dulled the memory. During this 1901 trip, he talks about spending considerably time in Chinatown, the oldest Chinatown in North America and still one of the largest Chinese enclaves outside of Asia. This is a period map showing that Chinatown (circled) is less than a 15-minute walk from Crowley’s hotel, so an easy jaunt for him during his stay.

Chinese began arriving in San Francisco with the Gold Rush of 1849, however many prospered more opening shops instead of becoming gold prospectors themselves. Upon seeing their hard-working ethic, the builders of the Transcontinental Railroad employed the Chinese in 1863 for the Central Pacific Railroad, with estimations that more than 20,000 Chinese laborers made up the majority of the workforce. Sadly, these men earned a half to two-thirds of their Euro-American counterparts and their contribution has literally been white-washed from many historical records. As seen in the images below, the famed completion image — commonly known as “The Champagne Photo” — by photographer Andrew J. Russell contains nary a Chinese worker as part of the workforce.

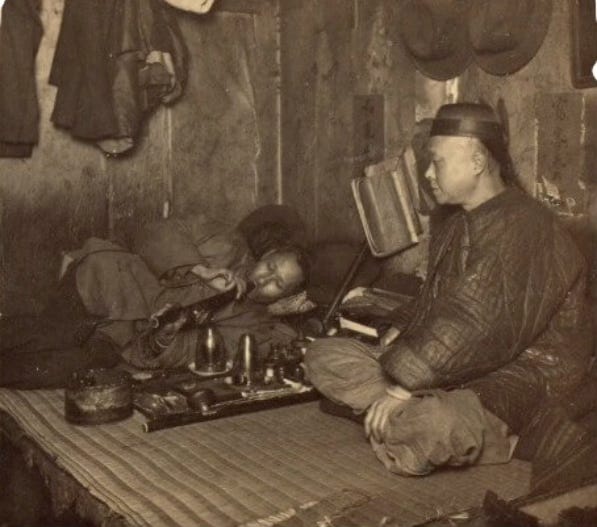

When the railroad was completed in 1869, some of the Chinese continued to move eastward and establish new Chinatowns in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. Many went back to San Francisco where Chinatown essentially became its own domain within the city. Corrupt associations known as tongs were established by the Chinatown residents, with their own criminal enforcement, banks, and legal centers independent of San Francisco proper. These criminal gangs fought for dominance in the streets of Chinatown, with various massacres that would rival any scene from The Godfather movie. With thousands of impoverished immigrants packed into unsanitary tenements, the gangs took advantage of the destitution in the establishment of vices; namely, gambling parlors, brothels, and opium dens.

Since the tongs had their own form of “police” in Chinatown, the San Francisco law enforcement mostly ignored the opium den trade. As one British journalist attested in the 1880s, “Occasionally, when the police are short of funds, they make a descent on some of the dens but, as a rule, the proprietors are left unmolested.” Around this same time, the San Francisco Call (the newspaper of the era) estimated there were approximately 300 opium dens in the city with signs above their doors reading — in Chinese calligraphy — PIPES AND LAMPS ALWAYS CONVENIENT.

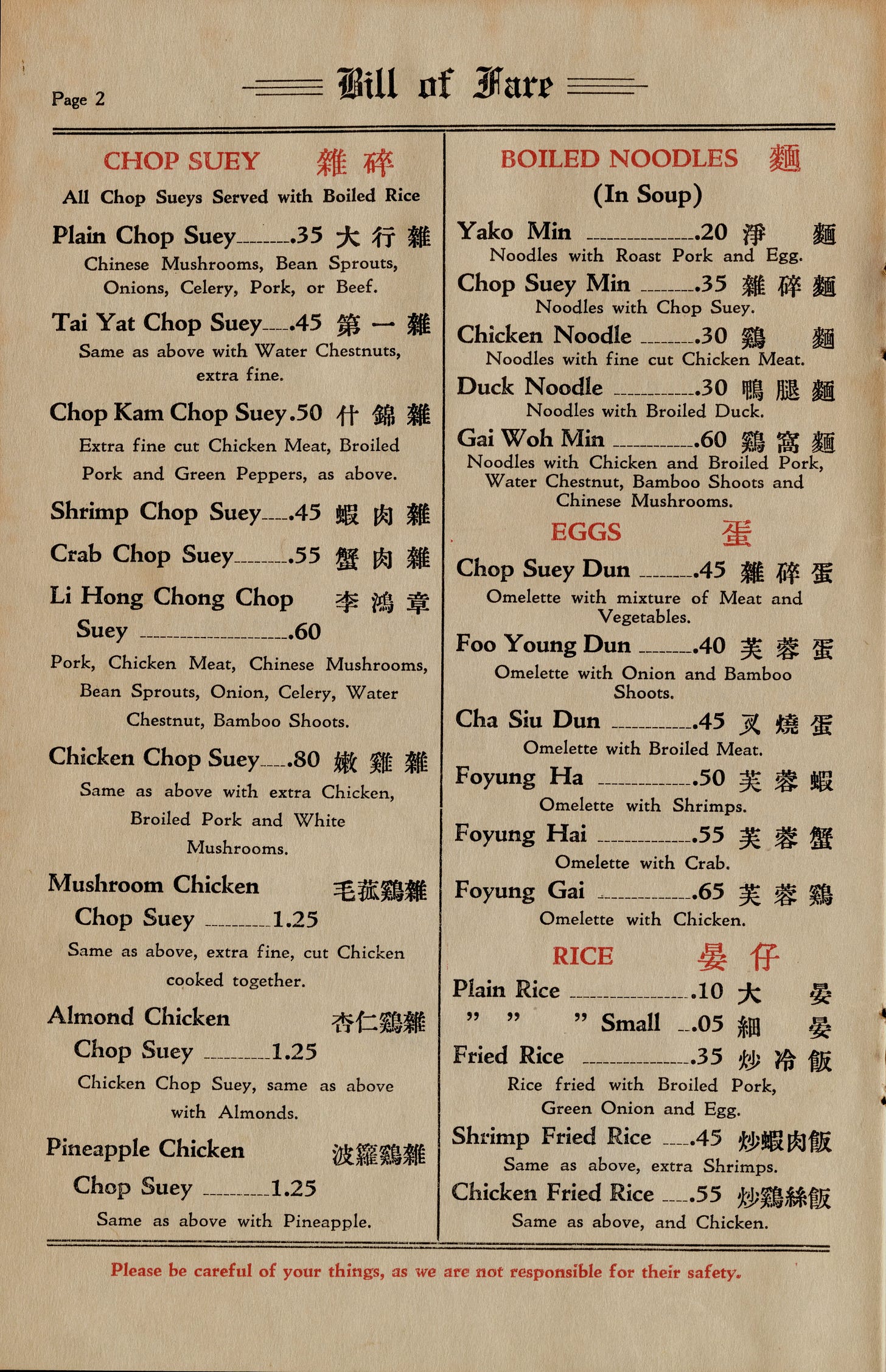

It comes as no surprise then, that Aleister Crowley would frequent his first Chinatown so often, knowing how readily available opium was at this time. However, this is not an investigation into his drug usage; simply an analysis of where he went and why, coupled with what he may have dined upon during those travels. The first Chinese restaurant in America, Macao & Woosung, was opened during the Gold Rush on the corner of Kearny and Commercial streets, in the heart of Chinatown. At the time, it was an all-you-can-eat buffet for $1.00. Urban legend states that a group of drunken miners stumbled into the restaurant when it was about to close. Making a ruckus about being hungry, the owner of the restaurant, Norman Asing, didn’t want to cook anything from scratch, so he mixed up scraps of leftovers from his Chinese customers, quickly tossed them in a wok with a bit of soy sauce and broth, and thus the miners were sated and thrilled.

The Cantonese dish tsap seui ( 杂碎, “miscellaneous leftovers”) was born and translated as “chop suey.” Another origin story comes from 1896’s New York City where Li Hongzhang, a visiting diplomat, was hosting some American guests for dinner. Unsure about serving authentic Chinese food, Hongzhang requested his personal chef prepare a dish that would appeal to both Chinese and American palates, with chop suey being the result. Both of these origin stories are suspect, according to Andrew Coe’s book, Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States. In it, he states:

… there’s little doubt that this dish — in its manifestation as a stir-fried organ meat and vegetable medley — originated in the Sze Yap area around Toishan. A distinguished Hong Kong surgeon named Li Shu-Fan reminisced about a childhood visit to Toishan, which was his ancestral home:

“I first tasted chop suey in a restaurant in Toishan in 1894, but the preparation has been familiar in that city long before my time. The recipe was probably taken to America by the Toishan people, who, as I have said, are great travelers. Chinese from places as near to Toishan as Canton and Hong Kong are unaware that chop suey is truly a Chinese dish, and not an American adaptation.”

Regardless of its origin, Americans began a “chop suey craze” as they discovered Chinese food and I have no doubt it would have been one of many meals Crowley would have feasted on before or after his visits to the notorious opium dens.

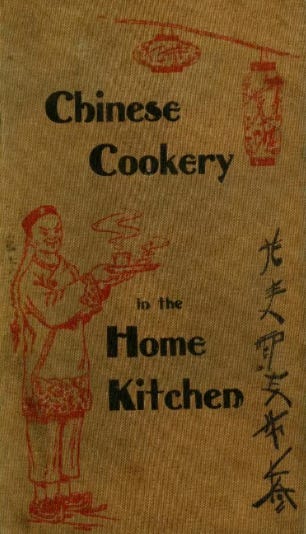

Wanting to share recipes with you, I dug into the oldest English-written Chinese cookbooks I could find for historical chop suey recipes. From 1911’s Chinese Cookery in the Home Kitchen edited by Jessie Louise Nolton:

This, as well as a 1917 Chinese cookbook’s version, were ever-so-slightly “Americanized” in their omission of offal. Per Andrew Coe’s research cited above, authentic Chop Suey would include organ meats so in my attempt, I used duck gizzards.

Ingredients:

1/2 lb. lean pork, sliced in long, thin strips

1/2 lb. chicken or duck gizzards, sliced thin

1 cup celery, sliced crosswise

4 or 5 “Chinese potatoes” aka water chestnuts, sliced

1 Spanish onion, sliced thin

1 cup mushrooms (Note: not canned! Dried Chinese shiitake mushrooms are excellent and the soaking broth can be used in this dish, or fresh shiitake, wood ear, or enoki, or a combination thereof)

1 cup fresh bean sprouts

1 tsp. cornstarch, dissolved in:

1/2 cup chicken broth or the mushroom water from reconstituting dried mushrooms

1 tbsp. light soy sauce

1 tbsp. dark soy sauce

peanut or sesame oil for cooking

Cook in a wok, if possible, over very high heat and cook quickly.

With a tablespoon of oil in the hot pan, fry the pork and gizzards until half done. Add the onions, cooking a few minutes longer, then add the vegetables, tossing quickly for a minute or so. Very carefully add half the broth around the edges of the pan and cover to the steam the ingredients for two or three minutes. Add a bit more broth and continue to toss everything together, finishing up with the soy sauces.

Continue reducing the broth until a silky sauce coats the ingredients. Add the soy sauce and toss until well-coated.

Serve atop some steamed white rice and enjoy!