San Francisco - 1901, Cocktails

The Pisco Punch

Before we depart San Francisco for another port of interest, it is worth a special post about cocktails.

Historically, fermented beverages have been around since probably 10,000 BCE. The Chinese had been fermenting a concoction of rice, honey, and fruit since 7,000 BCE. There is evidence of wine grapes in what is now modern-day Iran that date to the mid-5000s BCE, and King Tut’s tomb (1323 BCE) boasted wine jars meticulously labeled with their year and vintner. Historians believe the modern day cocktail was born out of the British punch; a blend of spirits (or not, for teetotalers), fruit juice, and spices, and was served at social events such as hunting parties, balls, or garden parties. Such was the elegance of a punch, that specialty ladles were made for their serving. This one in my collection has a handle of twisted whale baleen and a Georgian-era coin set in the bottom. Relatively small, it only pours about one-and-a-half ounces.

The Golden Age of Cocktails occurred during the fifty-year span between the end of the American Civil War — 1865 — and the beginning of World War I, in 1914. The Industrial Revolution, as well as a fundamental shift in society in the late 1800s, became a time of innovation such as the invention of the electric light, passenger trains, flight, and the moving vehicle. Oxford University was the birthplace of the first known book about mixed drinks in 1827, entitled Oxford Night Caps by Richard Cook. Thirty-five years later, Jerry Thomas’ book, The Bartenders’ Guide — a complete cyclopedia of plain and fancy drinks, was written exclusively for bartenders, showing just how much the concept of a mixed drink proliferated. San Francisco’s own William T. Boothby wrote The World’s Drinks and How to Mix Them in 1891, in which the Sazerac cocktail appeared for the first time in print.

In San Francisco today, there still exists seven cocktail bars that were open during Crowley’s 1901 visit: The Old Ship Saloon (1851), Elixir (1858), Northstar Cafe (1882) Shotwell’s (1891), The Little Shamrock (1893), and Bus Stop Saloon (1900). This doesn’t take into account the beautiful bar located inside the Palace Hotel, or the myriad of others long since lost to time, including one that will become quite important to our investigation, The Bank Exchange.

Why all this hullabaloo about cocktails, might you ask? As it happens, the cocktail culture — specifically Pisco — was already part of the wild and wooly days of early San Francisco, thanks to Peruvians. Sounds odd, doesn’t it? I owe thanks to Camper English, a San Francisco-based cocktail historian, for this story he shared with me that made me think Crowley must have explored California’s signature cocktail of the age: The Pisco Punch.

Briefly, Spanish conquistadors planted grapevines in Peru in the 1500s where Catholic clergy missionaries thought it better to make their own sacramental wine instead of importing it from Spain. By the 1600s, this wine was being distilled into a brandy; then called aguardiente de uva, which meant “grape firewater.” As ships headed to California for the 1849 Gold Rush, they would stop at the port of Pisco to load up on the local brandy, hence the name-change of this heady spirit. By 1850, it was all the rage throughout San Francisco saloons, most notably at The Bank Exchange, quite a fancy establishment where Mark Twain was known to frequent.

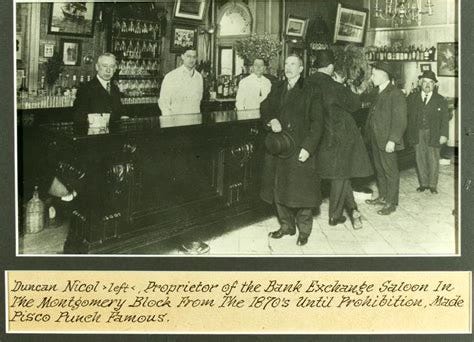

The important thing about the Bank Exchange Saloon was its bartender, Duncan Nicol (1852-1926) who made famous the Pisco Punch (not invented by him, as it pre-dates him at the bar). Like the Black Russian from the Hotel Metropole in Brussels, Belgium, the French 75 from Harry’s in Paris, France or the Negroni from Caffè Casoni in Florence, Italy, one did not come to San Francisco and not try the famous Pisco Punch at the Bank Exchange.

From Camper English’s book Doctors and Distillers:

The drink’s recipe was a secret that Nicol took to his grave when he died during Prohibition. The punch was widely reported to “make a gnat fight an elephant,” . . . [but] also produced a buzz “in the region of bliss of hasheesh and absinthe,” as a 1912 promotional pamphlet declared.

Bartenders have settled on [the ingredients being] pisco, pineapple syrup thickened with gum Arabic sap, and citrus. But that doesn’t explain the reported impact of the drink. Pisco scholar Guillermo Toro-Lira, as quoted in Gregory Dicum’s The Pisco Book, thinks he figured out the missing ingredient.

“It had to be cocaine,” said Toro-Lira. The theoretical cocaine could have been purified or come in the form of Peruvian cocoa leaves infused into Pisco. Cocaine had been a wonder drug and a frequent ingredient in patent medicines. Toro-Lira said, “That’s why it was a secret recipe — he (Nicol) didn’t want it exposed. I don’t know what form of cocaine he used, but I am 99.9% sure he used cocaine.”

So there we have it. There is no doubt in my mind that being the experimenter of all types of drugs, this was something that Aleister Crowley would have reveled in during his San Francisco stay.

Fortunately for me, San Francisco still being a cocktail-centric town, it was not difficult to find the ostensibly rare ingredient of pineapple gum syrup. I confess that before I bothered to look for it premade, I researched methods of making my own pineapple gum syrup (and even ordered the powdered gum Arabic). Finding those instructions a bit too daunting, I googled “pineapple gum syrup” and discovered several manufacturers, thrilled to acquire some from Liber & Co. If curious, the difference between using just pineapple juice and pineapple gum syrup is mouthfeel. There is a bit of unctuousness to the cocktail with this addition.

Here are the proportions, if you care to try this at home — and I heartily suggest you do (sans cocaine) — as it is quite a tasty.

2 ounces (60 ml) pisco (buy the best brand you can afford; this is something you do not want to skimp on).

.75 oz (20 ml) freshly squeezed lemon juice

.75 oz (20 ml) pineapple gum Arabic syrup

Add all the ingredients to an ice-filled cocktail shaker. Shake vigorously for 20 to 30 seconds at least, and strain into a well-chilled cocktail glass.

Please report back what you think, if you try this cocktail! I am certainly a fan.

Fascinating. Although I have difficulty with pineapple, I may be able to use pineapple gum Arabic. I love pisco sours.

Karen